The Compression Effect in Photography

Medium: my original post

The Compression Effect

There is a wonderful effect that I have been seeing more of lately which photographers refer to as compression, or “flattening” an image. A subject is framed against a background that appears larger than life — at a scale that our eyes do not see. It is stunning — check out the following shots by @pegs4days and @alexstrohl (who is probably my favorite photographer of all time).

It appears as if the photographer has compressed the space between the subject and the background, bringing the background close to the viewer. When I first saw these sorts of pictures, I was sure that the photographer had to take two separate photos at different magnifications, and photoshop them together in post-production into a single image. As I have learned and will explain, this is not the case.

A Misconception

Up until recently, I believed that the compression effect is induced by having a larger focal length. The logic ran as the following:

I want the background in my image to be large. To view the background as larger than what my eyes can see, I need more zoom. In order to achieve more zoom, I must choose to use a large focal length lens, like a 85mm lens instead of a 24mm lens, to make the background seem larger. Thus, the larger the focal length, the greater the compression.

This logic, however, is flawed. Greater focal length does not mean greater compression. In fact, focal length does not affect the magnitude of compression at all.

Distance, between you and the subject, is the only variable that causes differences in the strength of compression.

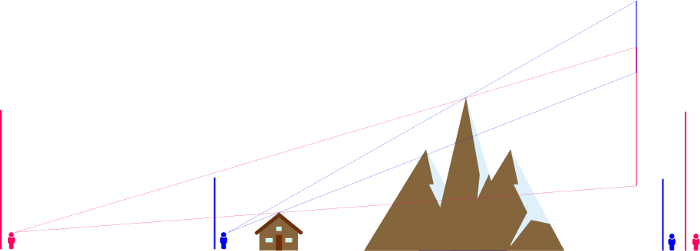

The compression effect is more clear with a diagram (I am a picture learner). In the diagram, two photographers take a picture of a house in front of a mountain. The blue photographer is much closer to the subject than the red photographer. For this example, let’s assume that the framing for both photographers are the same (they are using different focal lengths).

By drawing lines from the photographer’s eyes to the top of the house and the top of the mountain for each photographer, we can see the relative perceived differences in height between the house and the mountain for each person. The red photographer, who is standing further back, perceives the mountain taller (and larger) than the blue photographer, who is standing closer.

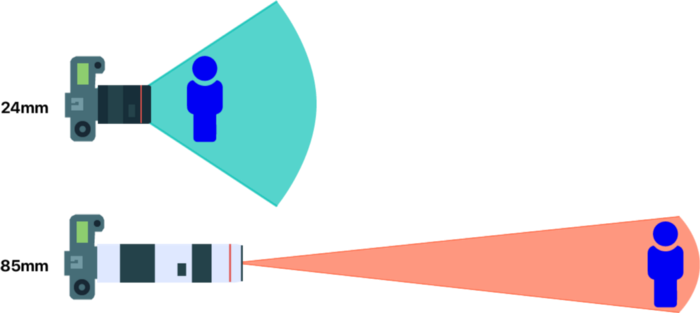

This seems perfectly logical — so where does the discretion come from? If you are like me, the misconception stems from the way photos are framed with different focal lengths. The effects of differences in focal length are twofold. A larger focal length not only means greater zoom, but also a narrower field of view. Similarly, a shorter focal length not only means less zoom, but also a wider field of view. In order to frame a subject the same (relative to the borders of the image), you must physically move a lot further back when you have more zoom (e.g. 85mm) than when you have less zoom (e.g. 24mm).

While having a larger focal length often leads to higher compression, it is certainly not a direct causation of the effect.

Examples

If diagrams are not your cup of tea, here are some photo examples (thank you Jess, Vylana, and Jerry).

In this first set of photos, I took photos of Jess (foreground) with different focal lengths, but from the exact same spot (about 20 feet away). I cropped the smaller focal length photo so that the two photos are framed the same. As you can see, the relative size of Vylana (background) does not change. The compression here is the same, because I (the photographer) have not moved.

This second set of photos shows the difference between the 200mm shot I took 40 feet away as opposed to the 200mm shot I took 20 feet away. As in the previous example, the left photo is cropped so that the framing would be the same. As is evident by the sizing of Vylana, moving backwards (even in the scope of 10s of feet) greatly changes the magnitude of compression.

What this means

The closer you are to your subject, the smaller the background appears relative to the subject. To achieve high compression, you must position yourself away from your subject. To master compression, you must move.

No matter what lens you use, the size of the background will remain the same unless you physically change the location of where you shoot the photo relative to the subject.

Learning how compression works has changed the way I approach photography. Whereas before I only moved laterally around my subject to find the best composition/framing of my shot, the knowledge of compression adds a new, extra dimension — movement back and forth.