Why Everyone Should Scuba Dive

Medium: my original post

“Ready? Take one giant step to clear the boat.”

Feeling like Neil Armstrong, I held my regulator and mask with my right hand and took one big leap into the ocean water. A cloud of white bubbles exploded around me, and my vision was clouded as my inflated BCD (buoyancy control device, essentially a vest you can inflate and deflate) brought me quickly back up to the surface. I switched from my regulator to my snorkel, and swam over to hold onto the trailing line off the back of the boat, where about ten other divers were clutched onto the thick rope anchored in the gentle current.

With one hand on the rope, I looked down at my surroundings for the first time, just to pop out a split second later. “Holy crap,” I called at Craig, my dive buddy. “Look down!”

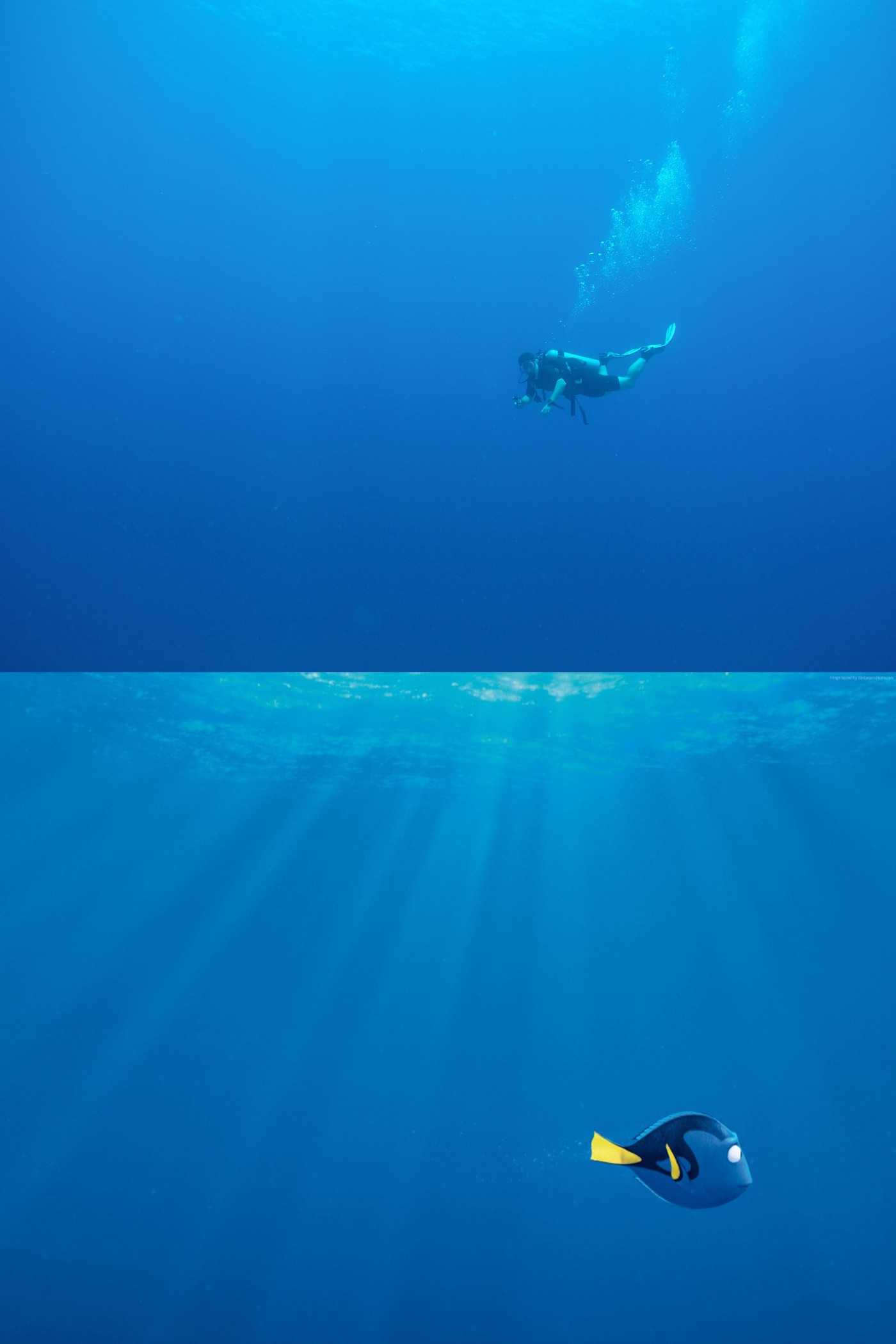

We were suspended 6 stories above the sea floor on translucent turquoise glass. For a brief moment I had a slight sense of vertigo as we stayed suspended at the surface. Below us was a massive reef, sprawling away from the sea wall, which dropped off steeply to a deep, impenetrable dark blue. An assortment of dark Caribbean fish, curious of our dive boat and the strange black figures flailing at the surface, gathered below us and were swimming in tight circles in the shade of the boat.

“Okay, now that everyone is in the water, let’s dive,” the dive leader called out. I snapped out of the trance and wheeled around to look at Craig. We signaled okay, switched our snorkel out for our regulator, and raised our low pressure inflator/deflator in the air with our left hand. Holding down the purge button, we vented all the air in the BCD and began our dive.

Without any air in the BCD, we descended at a rapid pace, kicking up from time to time to slow our fall. As we put distance between ourselves and the surface, our environment became steadily cooler and darker, as if we were passing through a subtle gradient. I gave my BCD two small squirts of air in order to achieve neutral buoyancy, and settled to take in the sights of the sea floor.

Touchdown. The world settled down at depth. All the anxieties, all the noise, all the excitement of my life at the surface was absent in this meditative state. All I heard was my own breathing — the Darth Vader-esque inhale, inevitably paired with the bubbly-sounding exhale — and nothing else. The seabed was textured into tiny dunes, and slow kicks into the sand sent silt swirling in an underwater sandstorm. Reaching upwards through the dunes were coral rocks, twisting and terraforming in alien-like shapes. On top of the eccentric rocks grew an uncountable amount of unique coral: purple skeletons, green spheres, pink stubs, periwinkle feathers. A gentle current drew parallel along the drop off, soft like a zephyr.

By this point, the dive leader had anchored the inflatable dive marker and gestured for us to follow him towards the drop off. Craig and I signaled okay to each other again, and we began kicking towards the drop off. At zero gravity, subtle movements allow you to glide in every direction with surprising control. On the way over to the wall, we passed over a lion fish settling into its nest, its lengthy poisonous spines of no concern as we steadily maneuvered above.

Over the reef ledge, the wall dropped down to about 100 feet, flattened out into a de facto ledge, and then fell straight down into darkness, thousands of feet towards the oceanic crust. The water over the cliff was the deepest shade of navy imaginable. There was nothing to see beyond the ledge; or rather, nothing you could see. I thought of Dory and Marlin in their quest for P. Sherman, 42 Wallaby Way, Sydney.

We swam into the current as we dove deeper and deeper, following the wall. 60 feet turned into 70, and 70 feet quickly turned into 85 feet, the deepest I’ve ever gone. On the bottom right corner of my dive computer, the “no deco time,” the maximum amount of time you have left at your current depth without having to do decompression stops on your ascent, had dropped down from 130 minutes at the surface to 20 minutes. At two and a half atmospheres of pressure, the air from the regulator rushed into my lungs with alarming ease; it is ironic how effortless it is to breathe when you are so far below the surface.

The 40 foot coral wall was impressive to behold, full of texture and personality. Coral jutted outwards irregularly, and there was plenty to look at within the nooks and crannies. The dive leader used a flashlight to highlight oceanic life amidst the darkness — arrow crabs, a king crab, eels, and one very, very large lobster. The giant lobster, with antenna that looked to be a foot long, stared at us with beady eyes that dared us to come closer.

As we made our way along the wall, I became aware of some peripheral movement above. I flipped my back towards the ocean floor and found about two hundred silver fish, each about 2 feet in length, swarming above. They moved slowly, in distinctly radial movements, playing follow the leader. From our position below, their large, dark silhouettes were intermittently broken by flashes of light reflecting off their bright scales. In such clear water, the large fish resembled a flock of confused condors, silent and nonsensical in their direction. It was one of the most beautiful scenes I have ever witnessed.

At 1800 PSI, we turned our dive. We allowed the current to gently bring us back towards the dive marker where we began our journey along the wall, and kicked upwards towards the daylight.

“One fish, two fish, red fish, blue fish. Black fish, blue fish, old fish, new fish. This one has a little star. This one has a little car. Say! What a lot of fish there are.” — Dr. Seuss

The coral wall itself teemed with life everywhere you looked. A plethora of Caribbean fish resided in and around reef formations, in varying group sizes. The fish darted in and out of small underwater caves with quick and twitchy movements. Schools of fish by the hundreds commuted on their ocean highways — we were immigrants in a brand new town, and it was rush hour. Keeping neutral buoyancy, it was easy to orient my body pointed directly down, like a pencil, to peek under the rock structures. I noticed that most of the fish on the reef were small, traveling in bright packs of blue, yellow, and red. Off to the side, where the reef was more sparse, a stingray could be seen sweeping the ground for garden eels. Close to the wall, a sea turtle passed by, swimming with the current.

Suddenly, a few fellow divers began signaling at something in the distance, pointing in a direction and placing a flat palm perpendicular above their masks. A shark had been spotted!

Shark! I had thought about the prospect of seeing a shark while diving at great lengths, and with a certain amount of fear. Seeing a shark up close, and in open water nonetheless, should have been terrifying, but it was not. In fact, it had the opposite effect: the confrontation is humbling, awe-inspiring, and serene. We all floated, suspended in time and mutual experience, as the shark snaked slowly towards us. It was about 6 feet in length, grey with tiny black pupils, with a triangular tail and round nose.

The shark stayed close to the wall, and then made a large loop around and swam once again towards us. Towards me, to be specific. It glided right underneath, maybe 3 feet below at maximum. Pure wonder filled the void of fear and anxiety. The shark moseyed around for a moment longer, and then disappeared into the distance off the edge of the wall, continuing on its way. I took an extra-long breath and exhale. Underwater, you can’t talk — you just feel.

At 700 PSI, our dive was over. Craig and I swam upwards to a depth of 15 feet, where we made a 3 minute safety stop to ensure most of the residual nitrogen in our bodies had a chance to escape through our lungs. The captain had thrown over a weighted PVC bar tied to 15 feet of rope so we could hang onto the bar while we waited for our dive watches to clear us for resurfacing.

While we floated in the water holding onto the bar, shaded by our dive boat above, the school of large silver fish from before returned. They gathered around us, as if they knew our time was up in the Caribbean and we wanted an encore. As we rode out the last of our tank, watching the school loop around us, it was difficult not to feel emotional. With this dive, I had definitely caught the diving bug.

I will be back in the ocean again.